Gamification, Presence and Awareness (Part 1/4)

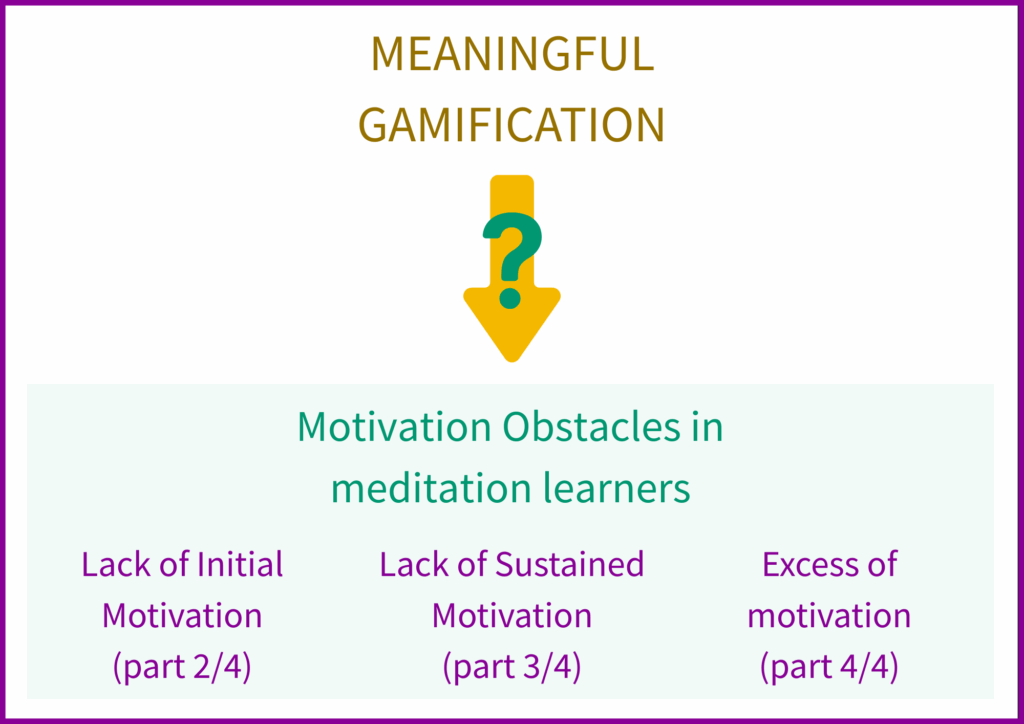

It is now time to explore the potential of meaningful gamification towards learning meditation. After having done the first assessment on this topic (Coquillard, 2025), some specific elements became especially significant within this endeavor, including how motivation is approached. After deepening my research, I continued to discover a very limited amount of research and information on the direct correlation of meaningful gamification in my learners’ context. However, when I started to use motivation as a keystone for research towards that relationship, I found a large amount of supportive research between meaningful gamification and the learning context in meditation.

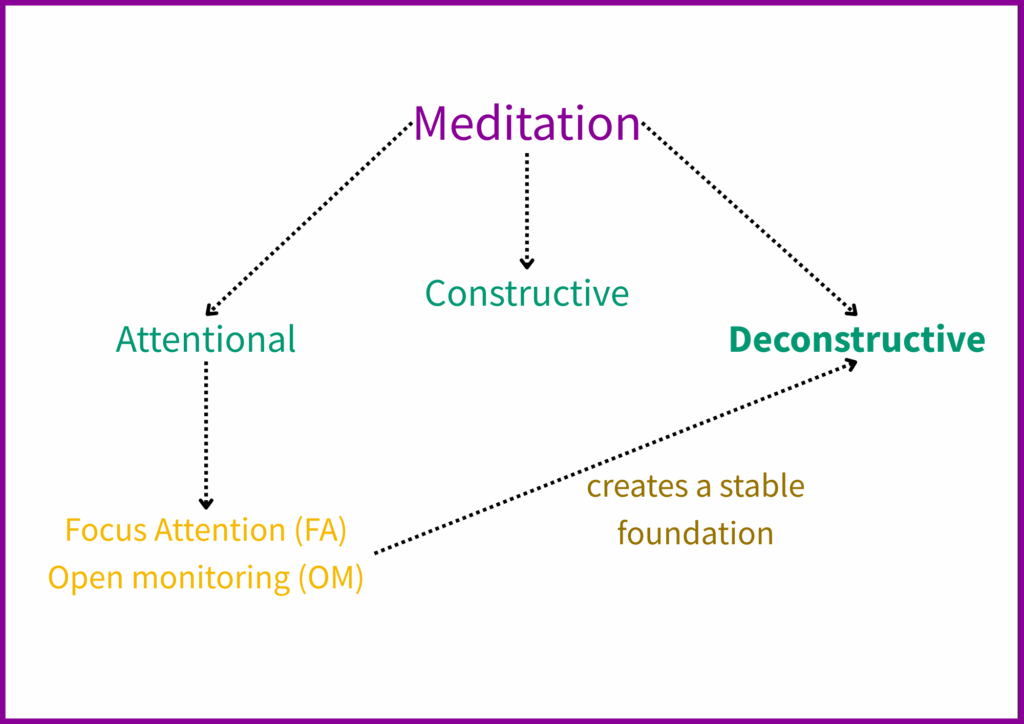

In scientific literature, the terminology to describe the type of meditation in which our learners are involved is called deconstructive meditation, the process of exposing the nature and dynamics of mind itself (Dahl, Lutz & Davidson, 2015). The purpose of this meditation process is to free oneself from a translation of reality made by the mind to clearly reveal that reality without bias.

From a practical point of view, the foundation required for this type of meditation lies in the more commonly researched type of meditation called attentional meditation, that includes focused attention (FA) and open monitoring (OM) (Dahl, Lutz & Davidson, 2015). These are also elements present in mindfulness.

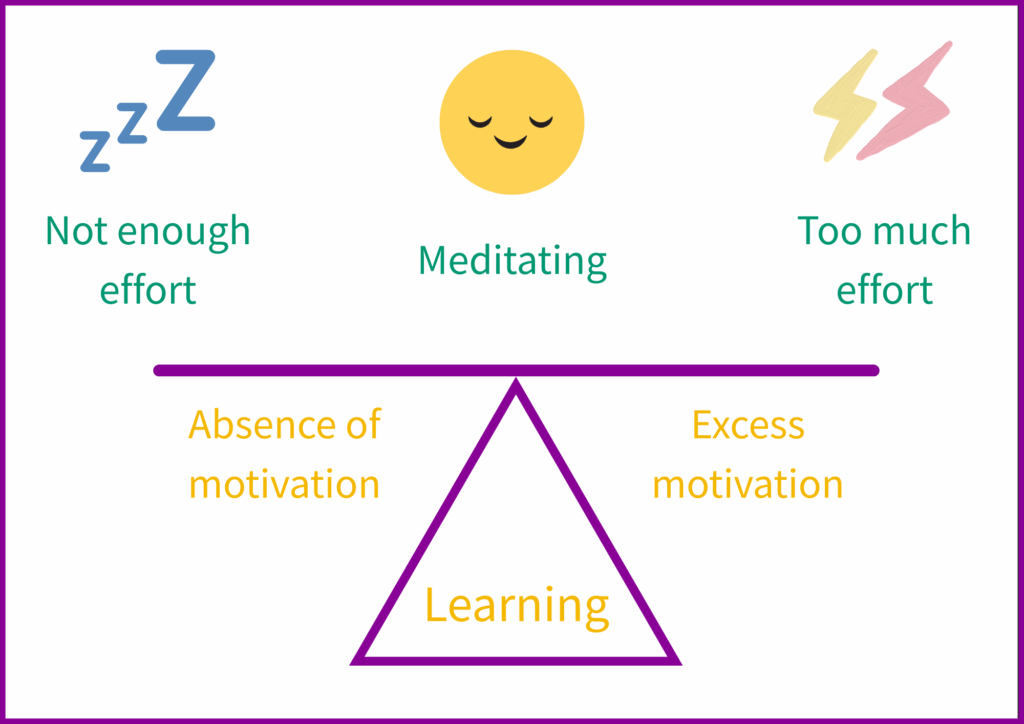

Much research has been done on FA and OM and the main obstacles that block the learning process (Ramírez-Barrantes et al., 2019). It is also a complex issue and to simplify it research show the need to have a balance between too much effort and not enough, between enough motivation to be engaged but not to the point of creating tension and being too goal oriented (Britton et al , 2014).

In terms of more specific real-life examples, a recent study shows how teenagers’ obstacle to meditation is a lack of motivation (Galla, 2024). Students don’t see the reason why they must do it, so they simply will not engage in it. As well as not perceiving the evident potential benefit for it, and on the other hand they don’t connect with the way it is presented to them. In both cases, this is an example of how initial motivation can be an issue.

Another example taken from a Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program with adult learners (Yavuz Sercekman, 2024). MBSR uses actively FA and OM types of meditation in a clinical setting which connects perfectly with our learners’ context (Brown et al, 2022). The study explains that despite the positive result of learning mindfulness on adult’s overall health and well-being, the subjects had difficulties in maintaining consistency in their motivation and engagement (Yavuz Sercekman, 2024). This analysis becomes an example of how a lack of sustained motivation can be a problem.

It is difficult to find field experience peer reviewed studies on the ‘excess’ of effort and motivation in terms of hindrance to meditation. There are however multiple articles available from experienced meditation teachers and researchers exposing the issue of being too aggressive in one’s practice, being too goal oriented with no sense of fun nor compassion while meditating (Kabat-Zinn, 2017; Amaro, 2018).

We have now identified three types of obstacles: lack of initial motivation, lack of sustained motivation, and ‘excess’ motivation. The link between gamification and motivation has been explored over the last decade and while there are still controversies, misunderstandings and more studies to be done, research shows that gamification has an impact on learners’ motivation (Li, Hew & Du, 2024; Rivera & Garden, 2021; Alsawaier, 2018). It is now time to evaluate the real impact of gamification on our learners’ motivational issues.

Continue to Gamification, Presence and Awareness (Part 2/4)

References:

Alsawaier, R. S. (2018). The effect of gamification on motivation and engagement. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 35(1), 56-79.

Amaro, A. (2018). ‘I’m Not Getting Anywhere with my Meditation…’: Effort, Contentment and Goal-directedness in the Process of Mind-training. Buddhist Studies Review, 35(1-2), 47-64.

Britton WB, Lindahl JR, Cahn BR, Davis JH, Goldman RE. (2014). Awakening is not a metaphor: the effects of Buddhist meditation practices on basic wakefulness. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Jan;1307:64-81. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12279.

Brown, K. W., Berry, D., Eichel, K., Beloborodova, P., Rahrig, H., & Britton, W. B. (2022). Comparing impacts of meditation training in focused attention, open monitoring, and mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy on emotion reactivity and regulation: neural and subjective evidence from a dismantling study. Psychophysiology, 59(7), e14024.

Chapman, J. R., Kohler, T. B., Rich, P. J., & Trego, A. (2025). Maybe we’ve got it wrong. An experimental evaluation of self-determination and Flow Theory in gamification. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 57(2), 417-436.

Coquillard, A. (2024). Assessment task 1 – Literature review in educational design graduate certificate unit EDF5768 – Educational design. Monash University.

Coquillard, A. (2025). Assessment task 1 – Compendium in educational design graduate certificate unit EDF5772 – Innovations in technologies and pedagogical practices. Monash University.

Dahl, C. J., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2015). Reconstructing and deconstructing the self: cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice. Trends in cognitive sciences, 19(9), 515-523.

Donald, J. N., Bradshaw, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Basarkod, G., Ciarrochi, J., Duineveld, J. J., … & Sahdra, B. K. (2020). Mindfulness and its association with varied types of motivation: A systematic review and meta-analysis using self-determination theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(7), 1121-1138.

Galla, B. (2024). How motivation restricts the scalability of universal school‐based mindfulness interventions for adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 18(3), 129-136

Ge, Y., & Han, T. (2021). MindJourney: Employing gamification to support mindfulness practice. In Advances in Usability, User Experience, Wearable and Assistive Technology: Proceedings of the AHFE 2021 Virtual Conferences on Usability and User Experience, Human Factors and Wearable Technologies, Human Factors in Virtual Environments and Game Design, and Human Factors and Assistive Technology, July 25-29, 2021, USA (pp. 228-235). Springer International Publishing.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2017). Common obstacles to practice. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1713-1715.

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: game-based methods and strategies for training and education. John Wiley & Sons.

Karadjova, K. (2018). Mindfulness and gamification in the higher education classroom: Friends or foes?. In 4th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAD’18) (pp. 1089-1097). Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València.

Krishnamurti, J. (1956). Education and the significance of life. New-York: Haper Collins publishers.

Li, L., Hew, K. F., & Du, J. (2024). Gamification enhances student intrinsic motivation, perceptions of autonomy and relatedness, but minimal impact on competency: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Educational technology research and development, 72(2), 765-796.

Li, M., Ma, S., & Shi, Y. (2023). Examining the effectiveness of gamification as a tool promoting teaching and learning in educational settings: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1253549

Ling, L. T. Y. (2018). Meaningful Gamification and Students’ Motivation: A Strategy for Scaffolding Reading Material. Online Learning, 22(2), 141-155.

Malone, T. W., & Lepper, M. R. (2021). Making learning fun: A taxonomy of intrinsic motivations for learning. In Aptitude, learning, and instruction (pp. 223-254). Routledge.

Mullins, J. K., & Sabherwal, R. (2018). Beyond enjoyment: a cognitive-emotional perspective of gamification.

Nicholson, S. (2015). A recipe for meaningful gamification. Gamification in education and business, 1-20.

Norbu, C. N. (2013). The Mirror: Advice on Presence and Awareness (dran pa dang shes bzhin gyi gdams pa me long ma). Religions, 4(3), 412-422.

Ramírez-Barrantes, R., Arancibia, M., Stojanova, J., Aspé-Sánchez, M., Córdova, C., & Henríquez-Ch, R. A. (2019). Default Mode Network, Meditation, and Age‐Associated Brain Changes: What Can We Learn from the Impact of Mental Training on Well‐Being as a Psychotherapeutic Approach?. Neural Plasticity, 2019(1), 7067592.

Rivera, E. S., & Garden, C. L. P. (2021). Gamification for student engagement: a framework. Journal of further and higher education, 45(7), 999-1012.

Sailer, M., & Homner, L. (2020). The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educational psychology review, 32(1), 77-112.

Tan, M., & Hew, K. F. (2016). Incorporating meaningful gamification in a blended learning research methods class: Examining student learning, engagement, and affective outcomes. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32(5).

Tanrıkulu, G., & Demirel, B. (2023). Gamification in Mindfulness Mobile Applications: The Effects of Rewards on Purchase Intention. Optimum Ekonomi ve Yönetim Bilimleri Dergisi, 10(1), 125-142.

Thomma, N. (2025). Gamified Mindfulness: A Novel Approach to Nontraditional Meditation (Bachelor’s thesis, University of Twente)

Wang, C. J., Liu, W. C., Kee, Y. H., & Chian, L. K. (2019). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the classroom: understanding students’ motivational processes using the self-determination theory. Heliyon, 5(7).

Whitton, N., & Moseley, A. (2019). Playful learning. Events and activities to engage adults. New York.

Wuyts, P. (2020). From Excess to Exhaustion: The Rise of Burnout in a Post-modern Achievement Society. In Perception and the Inhuman Gaze (pp. 205-217). Routledge

Xi, N., & Hamari, J. (2019). Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction. International Journal of Information Management, 46, 210-221.

Yavuz Sercekman, M. (2024). Exploring the sustained impact of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program: a thematic analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1347336.